Have You Ever Wondered Why People Lack Empathy?

Why friends sometimes shun each other when they should be there instead.

Denise Cummins, Ph.D.

Her research interests include the evolution and development of higher cognition in artificial and biological systems. Her experimental investigations work focus on Causal Cognition, Social Cognition, and Moral Cognition. The aim of this research is investigatingand explaining characteristics ofhigher cognition that emerge early in development, persist into adulthood, and are prefigured in the cognition of non-human animals.

Latest posts by Denise Cummins, Ph.D. (see all)

- When Emotional Intelligence Is Used To Manipulate People - Jun 17, 2015

- What Makes 50 Shades Of Grey So Successful? - Jun 17, 2015

- Here Are The 3 (Surprising) Keys To Success - Jun 17, 2015

You have probably noticed how some people seem to lack empathy and wondered why. Research offers an explanation.

“You OK? You seem distracted”, asks Alice’s coworker.

“Yes, I’m OK”, Alice responds. “It’s just that my mother is in the hospital again, and I’m not sure she’s going to make it this time.” Alice’s voice cracks, and she reaches for a tissue to wipe her tears. When she looks up, she is surprised to find her coworker has vanished.

To make matters worse, her coworker avoids her for the rest of the day. He is even hostile when Alice asks for information she needs to complete a report.

Later that evening, her coworker sends her an email that simply says, “Sorry. Couldn’t take it.”

Most of us have had interactions like this that leave us scratching our heads. We can reverse the sexes in the above scenario, or have both parties be the same sex. It doesn’t matter. It still surprises and chagrins us when people we consider friends—decent, kind people—seem to abandon us when we most need emotional support. They are clearly not sadists who delight in the suffering of others or psychopaths who are indifferent to it. So their behavior is perplexing.

This kind of interaction can lead to anger, judgment, and recriminations—the “you don’t care about me” outrage response. But here is the problem: Both parties feel their feelings have been trampled.

The Empathy Response Can Lead to Emotional Overwhelm

Consider what happens inside us when we view the suffering of others. When we experience physical pain or emotional distress ourselves, a neural circuit becomes activated (anterior cingulate cortex—or ACC–and insula). Neuroscientific research(link is external)shows this same circuit gets activated when we see others suffer pain or emotional distress. So seeing the suffering of others causes us to suffer as well.

Although this response is crucial for social interaction, it is indeed unpleasant. If that circuit is hit too frequently (excessive sharing of others’ negative experiences), it can lead to emotional burnout.

And so people develop strategies for protecting themselves. Some do what Alice’s coworker did—put physical and emotional distance between themselves and the suffering person. Some stay present but emotionally dissociate, which the sufferer usually experiences as emotional abandonment.

Coping with the Emotional Overwhelm of Empathy

A crucial part of socialization is learning how to protect oneself from being overwhelmed by the suffering of others while still giving them the support they need and deserve.

Research suggests that the answer to this dilemma may be compassion training.Compassion is defined(link is external) as a feeling of concern for the suffering of others (rather than experiencing distress in the face of the suffering of others.) Programs aimed at training compassion(link is external) have been found to foster prosocial (helping) behavior while evoking a feeling of emotional well-being.

Recent research(link is external) led by Max Planck scientist Olga Klimicki showed that compassion training actually affects which neural circuits are activated when viewing the suffering of others.

This was the basic design of the experiment:

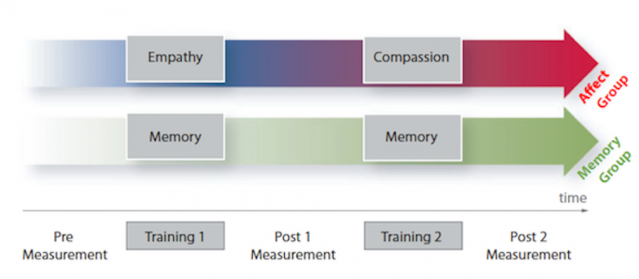

The design of an fMRI study on compassion training

The affect group viewed three blocks of video clips that consisted of a high-emotion and a low-emotion video clip (10-18 seconds long). The clips were taken from newscasts or documentaries. The high-emotion video showed people suffering physical or emotional distress. The low-emotion videos showed everyday scenes that did not include suffering. fMRI brain scans were taken while the women viewed the videos. After each video, the women rated how much empathy, positive feelings and negative feeling they had experienced while seeing the video. They were told that “empathy” meant how much they shared the emotion of the persons in the video clips.

The first session was the baseline—the women simply viewed the videos and their natural responses were recorded. Following this pre-training viewing session, the women received “empathy training” to enhance their empathetic responses. This training consisted of instructing them to focus on resonating with the suffering they were viewing. The second viewing session followed this training. Following this, they received “compassion training” which consisted of a meditation for directing love and compassion toward themselves and others. They then viewed the third and final set of videos. (A control group completed a memory task that consisted of learning lists of neutral words.)

The results were quite striking: As expected, the women showed more distress to the high-emotion clips than the low-emotion ones, both in their fMRI scans and their own ratings. The scans showed activation of the “empathy circuit” (ACC and insula). Their distress was enhanced following empathy training—greater activation in their empathy circuitry, higher negative emotion ratings, and lower positive emotion ratings.

But importantly, compassion training reversed these effects: Negative emotion ratings returned to baseline levels, positive emotion ratings surpassed baseline levels, and a brain circuit associated with reward and affiliation became activated (medial orbitofrontal cortex and striatum).

The researchers concluded that compassion can be trained as a coping strategy to overcome empathic distress and strengthen resilience. Rather than feeling overwhelmed by the suffering of others, those trained in compassion can offer help while simultaneously deriving peace and satisfaction from reducing the suffering of others.

Final note: You may be wondering why only women served as participants in the study. The answer can be found here.

Dr. Cummins is a research psychologist, a Fellow of the Association for Psychological Science, and the author of Good Thinking: Seven Powerful Ideas That Influence the Way We Think.(link is external)

Dr. Cummins is a research psychologist, a Fellow of the Association for Psychological Science, and the author of Good Thinking: Seven Powerful Ideas That Influence the Way We Think.(link is external) More information about me can be found on my homepage(link is external). Follow me on . And on +.